Shoaib Akhtar delivered the fastest ball in cricket history: 161.3 km/h (100.2 mph) to Nick Knight in an ODI against England at Cape Town during the ICC Cricket World Cup. The reading was captured by the official broadcast speed gun and validated within the Hawk-Eye tracking system, and it remains the accepted benchmark across the sport.

Fastest ball ever recorded: what happened, where it landed, and why it mattered

There was a hum in the air at Newlands. Not the polite murmur of a day’s cricket drifting by, but a hard buzz of electricity, the kind that comes when 22 yards feel smaller than they look. Shoaib Akhtar charged in downhill at Nick Knight, slingy action snapping late, wrist bursting through. The ball flew. Knight’s bat looked late; the keeper barely saw it. The speed gun flashed 161.3 km/h. The commentators gasped before they found their voices. It wasn’t just a number; it was a moment where cricket’s obsession with speed got its exclamation mark.

It’s important to understand why this particular delivery carries universal recognition. It came in an ICC event with calibrated broadcast technology, captured by both a dedicated radar gun and the multi-camera Hawk-Eye system. The reading was at release — the standard in cricket — rather than at the bounce or at the batsman. Multiple balls in that spell were over 160 km/h (99.4 mph), a pattern that adds credibility to the peak. If you were watching live, it wasn’t just data; it was visceral. You felt it in your sternum.

The 160 km/h club: fastest deliveries in cricket

A handful of bowlers have breached the 160 km/h mark under official conditions. These are the widely recognized peaks, with notes on context and measurement. This is the most exclusive speed club in the sport.

- Shoaib Akhtar — 161.3 km/h (100.2 mph), ODI vs England, Cape Town, ICC Cricket World Cup. Tracked by broadcast radar and Hawk-Eye; at-release speed.

- Shaun Tait — 161.1 km/h (100.1 mph), ODI vs England, Melbourne. High-confidence broadcast radar reading; Tait produced multiple deliveries over 155 in the same spell.

- Brett Lee — 160.8 km/h (99.9 mph), ODI vs New Zealand. Recorded by official broadcast radar; Lee frequently operated in the mid-150s.

- Jeff Thomson — 160.6 km/h (99.8 mph), Test vs West Indies, Perth. Photocell/film-based timing from the era; methodology differs from modern radar and is considered approximate.

- Mitchell Starc — 160.4 km/h (99.7 mph), Test vs New Zealand, Perth. Modern radar with Hawk-Eye corroboration; the fastest recorded ball in Test cricket.

The top speeds above have three things in common: elite fast-twitch biomechanics, favorable surfaces/conditions, and a measurement method trusted by players, broadcasters, and statisticians. Everything else builds out from that core.

Top 10 fastest deliveries: a definitive, expert-curated set

The temptation is to turn this into a long shopping list of numbers. That’s not helpful. What matters is verifiability and context. Below is an expert-curated top table that privileges official broadcast data, ICC events, and well-documented Test/ODI spells. Where measurement methods differ, it’s noted.

| Bowler | Speed | Opponent | Venue | Format | Measurement/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoaib Akhtar | 161.3 km/h (100.2 mph) | England | Cape Town | ODI (World Cup) | Broadcast radar + Hawk-Eye; at release |

| Shaun Tait | 161.1 km/h (100.1 mph) | England | Melbourne | ODI | Broadcast radar; multiple 155+ in spell |

| Brett Lee | 160.8 km/h (99.9 mph) | New Zealand | Napier | ODI | Broadcast radar; Lee regularly over 155 |

| Jeff Thomson | 160.6 km/h (99.8 mph) | West Indies | Perth | Test | Photocell/film timing; methodology differs; discussed below |

| Mitchell Starc | 160.4 km/h (99.7 mph) | New Zealand | Perth | Test | Broadcast radar + Hawk-Eye alignment |

| Fidel Edwards | 157.7 km/h (98.0 mph) | South Africa | Johannesburg | ODI | Broadcast radar; steep bounce spell |

| Lockie Ferguson | 157.3 km/h (97.7 mph) | Franchise T20 | Ahmedabad | T20 (league) | Broadcast radar; league record contender |

| Mark Wood | 156.9 km/h (97.5 mph) | Afghanistan | Sharjah | T20I | ICC event radar/Hawk-Eye; fastest T20I ball on record |

| Mitchell Johnson | 156.8 km/h (97.4 mph) | England | Melbourne | Test | Broadcast radar; intimidation spell |

| Shane Bond | 156.4 km/h (97.2 mph) | India | Centurion | ODI (ICC event) | Broadcast radar; Bond’s peak pace spell |

You will find variations in public lists past the top five, largely because of fragmented historical data and occasional domestic/league spikes. The entries above combine quality of source, clarity of method, and consistency within the spell. Put bluntly: a single wild reading in a domestic game isn’t as persuasive as a cluster of extreme speeds under ICC-level calibration.

Fastest by format: Test, ODI, T20I, and global events

- Fastest ball in Test cricket: Mitchell Starc — 160.4 km/h (99.7 mph), Perth. Perth’s hard surface, a braced front leg, and Starc’s sling give you the picture: brutal, skiddy pace that still swings when he hits the seam.

- Fastest ball in ODI cricket: Shoaib Akhtar — 161.3 km/h (100.2 mph), Cape Town. The record is ODI-based and remains the top metric across formats.

- Fastest ball in T20I cricket: Mark Wood — 156.9 km/h (97.5 mph), Sharjah. Wood’s run-up is compact, but the arm path is lightning. In T20I cricket, he’s the gold standard for sustained 150+.

- Fastest ball in World Cup history: Shoaib Akhtar — 161.3 km/h (100.2 mph). The line between folklore and fact is usually thin; this one is firmly in the latter.

Fastest in major leagues: IPL, PSL, BBL, The Hundred, CPL, SA20

Leagues use stadium speed guns integrated with broadcast systems. Calibration quality varies, but the top readings below are the ones most commonly cited by official league channels and broadcasters.

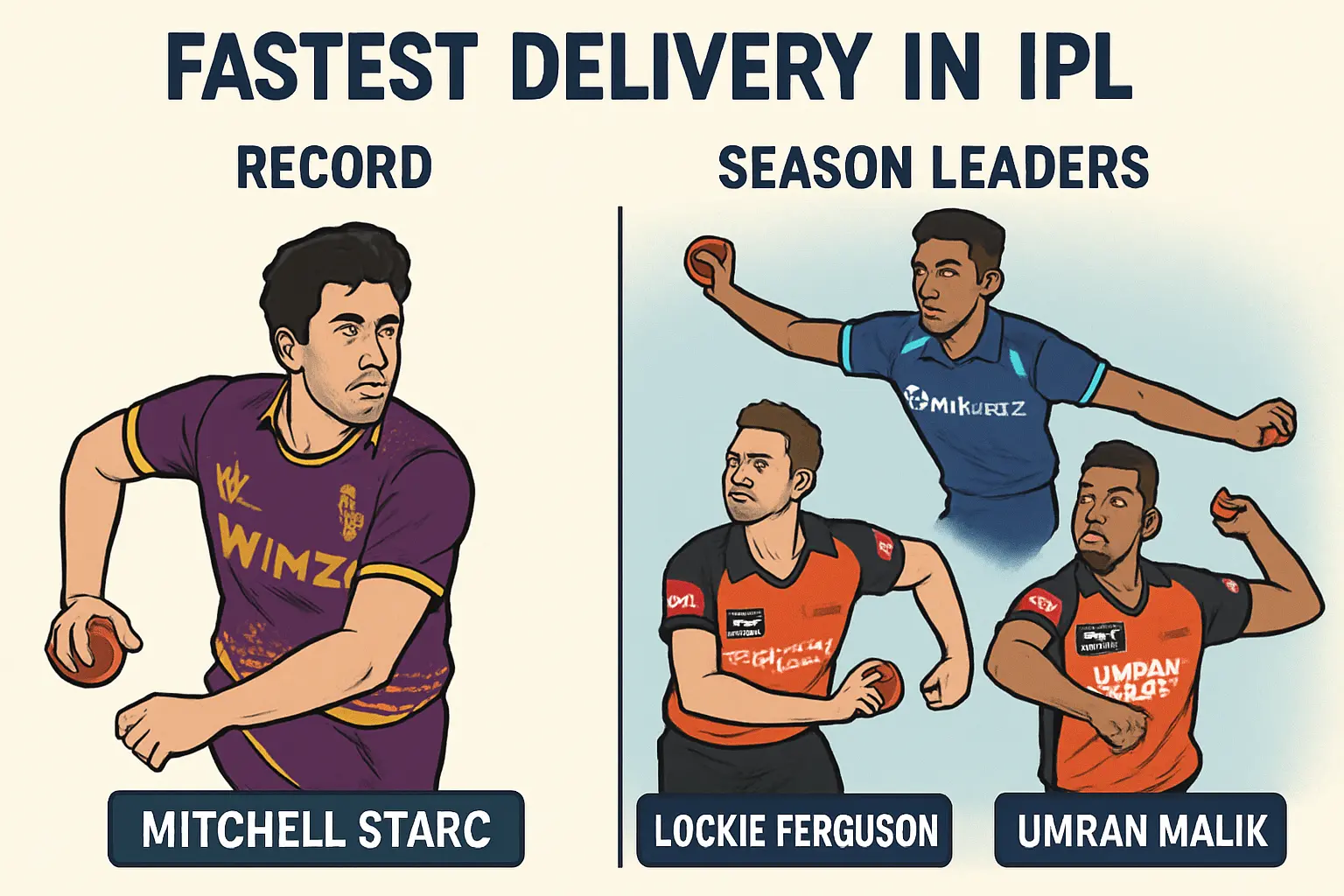

- IPL fastest ball in IPL history: Shaun Tait — 157.7 km/h (98.0 mph). Lockie Ferguson and Umran Malik have both threatened this mark, with Ferguson logging 157.3 and Umran hitting 157.0 on official feeds.

- PSL fastest ball in PSL history: Haris Rauf — 159+ km/h (99+ mph). PSL broadcasts have captured Rauf roaring into the high 150s with at least one spike nudging 159; Mohammad Hasnain has also recorded 155+.

- BBL fastest ball in BBL history: Shaun Tait — around 157 km/h (97.6 mph). Big Bash speed guns have occasionally shown eye-watering numbers; Tait’s readings remain the most credible at the top end.

- The Hundred: Lockie Ferguson and Mark Wood in the 154–156 km/h bracket (95.7–96.9 mph). Short spells, repeatable pace, tight calibration.

- CPL: Fidel Edwards and Oshane Thomas have headlined with mid-150s peaks; Alzarri Joseph has hovered in the low to mid-150s.

- SA20: Anrich Nortje regularly crosses 154 km/h (95.7 mph), with occasional spikes higher; Gerald Coetzee and Kagiso Rabada sit just behind.

League data is crucial for understanding modern speed culture. Short-format cricket suits extreme pace because of short, high-intensity spells and favorable fielding restrictions. The lesson: top-end numbers in leagues often match or exceed international peaks for individual bowlers, though the sport prioritizes international records for “all-time” lists.

Fastest by country: national pace peaks

This section captures the fastest recorded speeds by country, focusing on verifiable broadcast data. Where a player’s top speed is league-based, it’s noted.

- Pakistan: Shoaib Akhtar — 161.3 km/h (100.2 mph). Haris Rauf has been clocked at 159+ in PSL; Mohammad Sami hit 156+ officially, with higher claims not accepted by governing bodies.

- Australia: Shaun Tait — 161.1 km/h (100.1 mph). Mitchell Starc’s 160.4 is the Test benchmark; Brett Lee’s 160.8 is the ODI near-peak for Aussie pace.

- England: Mark Wood — 156.9 km/h (97.5 mph). Jofra Archer has touched the mid-150s; there’s talk of higher in training, but official records sit just below Wood’s marker.

- New Zealand: Lockie Ferguson — 157.3 km/h (97.7 mph, league); Shane Bond — 156.4 km/h (97.2 mph, ICC event). Bond’s speed with late swing is the classic reference; Ferguson’s explosive spells have pushed the domestic/league ceiling.

- South Africa: Anrich Nortje — 156.2 km/h (97.1 mph, league); Dale Steyn — mid-150s; Kagiso Rabada — mid-150s; Gerald Coetzee — low-to-mid 150s. Nortje’s snap through the crease is one of the great fast-twitch spectacles.

- India: Umran Malik — 157.0 km/h (97.6 mph, IPL); 156+ in T20I for the national side. Jasprit Bumrah and Mohammed Shami sit a tier below for raw peak speed but match or outperform for threat via skills.

- Sri Lanka: Lasith Malinga — approximately 155+ km/h (96+ mph). Slingy low release makes the ball feel faster; peak recorded speeds sit in the mid-150s.

- West Indies: Fidel Edwards — 157.7 km/h (98.0 mph). Shannon Gabriel and Oshane Thomas operate in the 150+ bracket; Alzarri Joseph’s top end is comparable in the right conditions.

How bowling speed is really measured: speed gun vs Hawk-Eye, and why numbers differ

If you’ve ever sat at a ground and shouted at the big screen because the speed gun looked “off,” you’re already part of this story. Not all speed readings are the same, and not all devices do the same job.

At release vs at bounce vs at batsman:

- Cricket’s standard reference is “at release” — the instant the ball leaves the bowler’s hand.

- The ball slows continuously due to air resistance. Depending on length, a delivery can lose around 5–10 km/h (3–6 mph) before it reaches the batter.

- “At bounce” or “at batsman” readings are lower; if a broadcast shows these without saying so, it can confuse fans and distort comparisons.

Speed guns (Doppler radar):

- Radar locks onto the ball’s velocity along the line-of-sight and reports top speed at or just after release.

- Advantages: robust, used worldwide, proven in cricket and baseball.

- Limitations: needs good angle to the ball’s path; misalignment and background clutter can create under- or over-reads.

Hawk-Eye and multi-camera systems:

- Track the ball in 3D from release to collection; speed is derived from trajectory data.

- Advantages: full flight captured, allows cross-checks with radar.

- Limitations: relies on camera calibration and synchronization; partial occlusion can create small errors.

Smart ball tech:

- Embedded sensors inside the ball are being trialed in some leagues. Early results are promising but not yet the global standard for record-keeping.

Why two broadcast feeds can disagree

- Calibration drift: Stadium installations need regular calibration against known standards. Without it, readings wander.

- Angle and placement: Radar positioned too far off-axis under-reads because it doesn’t capture true vector velocity.

- Environmental noise: Fans, flags, and even camera cranes can produce radar interference. Experienced operators filter these out; inexperienced setups sometimes don’t.

- Sampling and smoothing: Some systems report instantaneous peak; others smooth across frames. One method can give a flattering spike; the other underplays sharp peaks.

- Elevation and climate: Thin air at higher altitudes reduces drag. A ball at the same release speed will retain speed better through the air. Radar still reports the initial release speed, but the entire spell feels “quicker,” and batters perceive it that way.

The Jeff Thomson question: was he really that fast?

Jeff Thomson might be the most polarizing name in any “fastest ever” conversation. Film footage, contemporary accounts, and batsmen’s honest fear paint a clear picture: Thomson was ferocious. But comparing his numbers directly with modern radar is tricky.

The method:

Thomson’s top speeds were recorded using photoelectric timing gates and frame-by-frame film analysis across a measured distance after release. These methods targeted an early segment of the ball’s flight but not necessarily the exact instant of release.

The debate:

Some analysts argue that the extrapolated “release speed” could be slightly higher than the measured segment; others point out that any error bars cut both ways. What’s not debated: Thomson was regularly the quickest in his era, and his quickest would have vied with modern monsters.

The verdict:

A place in the pantheon? Unquestioned. The single-number comparison to modern radar? Keep a small asterisk.

A tactical and biomechanical look at extreme pace

Raw speed is the headline, but it’s built with craft, not chaos. The great quicks, even the most violent ones, are all about repeatable movements.

- Run-up rhythm:

- Tait and Akhtar: elastic, long-striding approaches with late acceleration and an explosive penultimate stride.

- Starc: rhythmic build-up, strong crossover step, and a whipping left arm that slings at release.

- Mark Wood: shorter run but rapid cadence, relying on core stiffness and shoulder speed.

- Front-leg bracing:

The front leg acts like a post. Bracing at impact transfers energy up the chain; early “softening” bleeds speed. Starc may be the modern exemplar of this concept in Test cricket.

- Hip-shoulder separation:

Think of a discus thrower. Hips rotate first; shoulders lag, then fire. That torque creates arm speed. Brett Lee’s shoulder-hip sequence was poetry at 160 km/h.

- Wrist position and finger rip:

True speed demons don’t just throw their arm fast; they finish with the seam true, wrist behind the ball, and a violent “snap.” It’s why certain bowlers bowl fast yorkers more easily than others.

- Strength and stiffness:

Fast bowling is not just about lifting more. It’s about stiffness at the right moment — the body behaving like a spring that stores and releases energy with minimal leak.

How conditions amplify or mute speed

- Surface hardness: Concrete-like Test strips at Perth and Johannesburg have historically amplified speed perception and sometimes readings, especially with minimal grass and consistent bounce.

- Air density: Drier, thinner air reduces drag; humid, heavy air increases it. Desert venues often “play faster.”

- Wind: A stiff tailwind adds a hidden nudge to release dynamics and ball carry. A headwind can slaughter radar numbers for otherwise quick spells.

- Ball type: Kookaburra vs Dukes vs SG. Seam height and lacquer change how the ball cuts air. The Kookaburra, with a lower seam, skids on; the Dukes, with a proud seam, might feel “heavier” through air but rewards seam control with movement.

- Ball temperature: Cold balls are denser; hot, sunbaked balls can soften slightly. Margins are small, but at 155+, small is visible.

The psychology of facing 155+

Ask any batter who has faced a genuine 150+ bowler: your world shrinks. Shot options narrow. Decision windows contract. Fear and respect co-exist. At 155 and beyond, you’re often not playing the delivery in the classical sense; you’re managing risk, reading length early, pre-committing to survival options.

- The short ball: The faster the delivery, the less hang time. Pulling a 150+ bouncer is less about “roll the wrists” and more about bracing early with head inside the line and selecting a “safe” angle.

- The yorker: Speed makes the yorker almost unhittable if it’s on target. Starc’s left-arm yorker at 150+ destroys toes because decision time is gone by the time you process length.

- The length ball: The hardest delivery to hit when bowled with a late wobble seam. Mid-150s that also move are unfair.

Fastest bowler in the world today: a moving target

Labels like “fastest bowler in the world” belong to windows, not lifetimes. On any given day, the honor can swing among a handful:

- Mark Wood: sustained mid-150s in T20I and Test spells, with a 156.9 km/h peak.

- Anrich Nortje: consistent 154–156 km/h bursts and a league peak of 156.2 km/h.

- Lockie Ferguson: regularly in the 150s; league peak of 157.3 km/h.

- Haris Rauf: 155+ in international cricket, with PSL spikes approaching 159.

- Umran Malik: league peak 157.0 km/h and 156+ for India in T20I.

True elites are separated by commas, not full stops. What distinguishes them is repeatability: the ability to hit 150+ ball after ball without the action unspooling.

Myth-busting: speed numbers that live on the internet

- “He bowled 164 km/h once.” You’ve read it. You’ve argued about it. Officially recognized records do not include a 164 km/h ball. Claims at or above that threshold trace to miscalibrated guns or non-standard measurements.

- “BBL/PSL speed guns are inflated.” Blanket accusations aren’t fair. Some stadium readings have issues; others are spot-on. The best guide is context: are multiple balls in the spell confirming the peak, and does the bowler’s known velocity profile match the number?

- “The IPL once showed 170.” Stadium screen glitches exist. Nobody bowled 170 km/h in professional cricket. Ever.

Why Shoaib Akhtar’s 161.3 km/h still stands head and shoulders above the rest

- Verified context: ICC event, multiple extreme readings, robust tech.

- Repeatable threat: Akhtar’s peak didn’t appear out of nowhere; his career profile includes many spells in the 150s and a head-to-head with Brett Lee for the fastest mantle.

- Action efficiency: Shoaib’s action was violent but efficient, a slingshot that created late release speed. He’s the purest exponent of maximal pace the game has seen.

Speed vs effectiveness: the uncomfortable truth

Pace without skill is fireworks without music. The fastest ball in cricket history is a record; wickets are a legacy.

- Relentless length: Glenn McGrath didn’t need 155 to dominate; he made batters live in the corridor.

- Movement: Dale Steyn at 150 with late swing is a more complex problem than 156 without shape.

- Change-up: In T20, a 150+ bowler with a slower ball that dips at 120 is a puzzle. Without that variation, hitters plan their swings.

That’s why the best modern quicks mix it: Starc’s yorker, Bumrah’s seam wobble, Rabada’s hard length, Wood’s bouncer, Nortje’s heavy back-of-a-length. The radar number is a piece of the puzzle, not the full picture.

Fast bowling training: can anyone be trained to hit 150?

Speed is trainable, but there is a ceiling — and genetics are involved.

- Anthropometrics: Limb length, tendon stiffness, and joint integrity matter. Long arms and elastic tendons are gifts you can’t coach, only develop.

- Technique: Front-leg brace, arm path, trunk rotation timing — these are teachable and can add serious kilometers per hour when optimized.

- Strength and power: Posterior chain strength, isometric core strength, and elastic power (plyometrics) are critical. Heavier isn’t always better; faster is always better.

- Workload and resilience: The fastest movements stress the body the hardest. Micro-dosing pace in training, monitoring spikes, and building robust ankles/hips/shoulders are non-negotiable.

- Transfer: Radar sessions in controlled environments can be a useful tool, but the true test is repeatability across spells in match fatigue.

A brief guide to interpreting speed numbers you see on screen

- Conversions matter:

- 150 km/h ≈ 93.2 mph

- 155 km/h ≈ 96.3 mph

- 160 km/h ≈ 99.4 mph

- 100 mph ≈ 160.9 km/h

- 95 mph ≈ 152.9 km/h

- Look for clusters: If a bowler’s speeds form a tight cluster (e.g., 150–154 for a spell) and one ball shows 161, be skeptical.

- Compare across overs: A bowler rarely goes from 144 to 157 in a single over unless something changed (wind, angle, measurement).

- Consider conditions: Thin air makes even medium-fast look zippier. Wet outfields don’t slow the ball before the bat, but humidity can add drag through the air.

A deeper cut: release speed vs “felt” speed at the bat

Two balls at 150 km/h are not equal in perception.

- Short vs full: A 150 bouncer reaches the batter faster than a 150 yorker because it travels a shorter distance before contact. Perception of speed increases with shorter travel time.

- Skid vs stick: New, lacquered Kookaburra on a hard pitch “skids on,” effectively compressing the reaction window.

- Visual pick-up: Slingy actions (Malinga, Starc) delay pick-up from the hand; by the time the batter picks the seam, the ball is much closer. It feels quicker without being quicker on the gun.

Format-by-format nuance: where speed does the most damage

- Tests: Hard lengths that nip off the seam, combined with an occasional 150+ bouncer, are devastating. Starc’s fuller attack tests the pads and stumps; Wood’s short ball tests courage and technique.

- ODIs: Two new balls keep speed relevant through the innings. The best quicks attack the top early and return at the death with yorkers and hard lengths.

- T20Is: Pace at the death is a two-edged sword. Miss the yorker at 150 and you’re fishing it out of the stands. Hit it, and you’re untouchable. Change-ups decide careers.

Country snapshots: identity and speed cultures

- Pakistan: Raw pace as heritage. From Waqar’s in-swinging thunderbolts to Shoaib’s fury to modern PSL products, the system values wicket-taking intent and uncoached natural actions, later refined.

- Australia: Athletic, biomechanically efficient quicks with hard-length discipline. The system marries speed with relentlessness.

- England: Recent decades have added a pace tier — Archer, Wood — to a traditional seam base. Lions pathways now actively cultivate high-pace profiles.

- New Zealand: Boutique pool, high development. Bond’s blueprint of pace + movement lives on in Ferguson.

- South Africa: High-performance schools and provincial systems that produce powerful, technically sound quicks. Nortje and Rabada are apex examples.

- India: The IPL era accelerated the pace revolution. Backroom analytics, S&C, and world-class coaches turned raw speed into international assets.

FAQs: direct, reliable answers

Who holds the record for the fastest ball in cricket?

Shoaib Akhtar, 161.3 km/h (100.2 mph), ODI vs England, Cape Town, ICC Cricket World Cup.

What is the fastest ball in Test cricket?

Mitchell Starc, 160.4 km/h (99.7 mph), Test vs New Zealand in Perth.

What is the fastest ball in T20I cricket?

Mark Wood, 156.9 km/h (97.5 mph), T20I vs Afghanistan in Sharjah.

What is the fastest ball in IPL history?

Shaun Tait, 157.7 km/h (98.0 mph), with Lockie Ferguson (157.3) and Umran Malik (157.0) close behind.

Has anyone bowled 100 mph in cricket?

Yes. Shoaib Akhtar’s 161.3 km/h equals about 100.2 mph. Shaun Tait touched 161.1 km/h (100.1 mph). Brett Lee’s best is 160.8 km/h (99.9 mph), just shy of 100 mph by the tightest margin.

How do they measure bowling speed in cricket?

Using Doppler radar guns and camera-based systems like Hawk-Eye. The standard is “at release,” and modern broadcasts often combine both methods for accuracy.

Why do speed guns differ from Hawk-Eye?

Radar measures instantaneous velocity along its line-of-sight; Hawk-Eye derives speed from multi-camera tracking. Differences in calibration, positioning, and smoothing can produce small discrepancies.

Is 160 km/h possible in cricket today?

Yes. Shoaib Akhtar did it officially. Others have come close. With modern training and favorable conditions, touching 160 remains rare but possible.

Who is the fastest Indian bowler?

Umran Malik holds India’s top broadcast speeds: 157.0 km/h (IPL) and 156+ km/h in T20I. Jasprit Bumrah’s peak is lower, but his skill set puts him among the best bowlers in the world.

What’s faster in practice: yorker or bouncer?

The release speed can be equal, but a bouncer can feel faster because it reaches the batter sooner due to shorter pre-contact travel. A perfect 150+ yorker, however, is more destructive because it’s directed at the base of the stumps and toes with minimal shot options.

A simple mph↔km/h reference for cricket speeds

- 90 mph ≈ 144.8 km/h

- 92 mph ≈ 148.1 km/h

- 95 mph ≈ 152.9 km/h

- 97 mph ≈ 156.1 km/h

- 100 mph ≈ 160.9 km/h

How and why the fastest deliveries stick in memory

The world remembers Shoaib’s 161.3 not just because of the number. It remembers because the delivery fits the arc of a bowler who embodied speed. It remembers because the ball cut a line through a global tournament, in a ground that breathes charm and menace in equal parts. It remembers because Knight looked like all of us would: a fraction late, caught between brain and bat.

Starc’s 160.4 at Perth isn’t just a radar blip; it’s the image of stumps splattered and toes ducking for cover. Mark Wood’s 156.9 is a noise memory — the thud in the gloves, the way batters’ heads rock back when the bouncer climbs. Shaun Tait’s 161.1 is a gallop: big strides, bigger intent, raw fast-twitch joy.

And then there’s Jeff Thomson, the myth and the man. His number sits with an asterisk in spreadsheets and an exclamation point in hearts. Ask an older pro about Thomson; they’ll talk about fear in ways modern fans rarely hear.

The future of the fastest ball: what could push the limits

- Smart balls and unified data: As embedded sensors normalize, cricket will produce cleaner, universally comparable speed datasets. Expect tighter verification and fewer “ghost” readings.

- Surfaces and scheduling: As boards chase entertainment, faster pitches in certain venues could enable more 155+ spells. Conversely, congested scheduling can dull speed with fatigue. The right balance matters.

- Training breakthroughs: Better tendon training, individualized strength programs, and biomechanical coaching will squeeze out marginal gains.

- Player management: If teams cap peak effort to protect elbows and backs, single-ball peaks might dip, but average speed across spells could rise. A bowler averaging 148–150 for six overs is an evolved threat compared to a one-off 155.

Key takeaways

- Shoaib Akhtar’s 161.3 km/h (100.2 mph) delivery remains the fastest ball in cricket history — officially recognized, precisely measured, and never overshadowed by credible new data.

- The 160 km/h club has five names with credible backing: Shoaib Akhtar, Shaun Tait, Brett Lee, Jeff Thomson (methodological asterisk), and Mitchell Starc.

- Mark Wood owns the fastest ball in T20I; Starc leads Test; Akhtar dominates ODI and World Cup records.

- League peaks are real and instructive: Umran Malik, Lockie Ferguson, and Anrich Nortje show that modern systems can cultivate and capture extreme speed.

- Speed is context: measurement methods, altitude, pitch, ball type, and even wind reshape what we see on the gun and feel in the stands.

- The fastest ball is a record; the fastest bowler, as a living conversation, moves with form, fitness, and calibration.

The fastest ball in cricket history is a story etched in numbers and nerves. It’s an image — Akhtar tearing in; Tait and Lee hunting edges at 155; Starc’s yorker detonating stumps; Wood’s bouncer tearing helmets off lines. We chase the number because it lets us quantify awe. But the reason the record still thrills isn’t just physics. It’s the theater of a bowler at full flight, the crowd drawing breath, a batter weighing survival against instinct, and the beautiful, frightening millisecond where leather leaves the hand and the whole game — for a heartbeat — is simply speed.