There’s a particular electricity when a one-day international turns into a sprint. The stadium starts to hum differently. You feel it in the drums on the hill, in the open palms under floodlights, in the bowlers’ hard stares when the ball keeps leaping over the rope. The fastest century in ODI cricket is the sport’s purest flex: one batter imposing pace on the game so completely that field settings, bowling plans, and even the clock feel irrelevant. It tests mechanics and mindset, the laws of leverage and timing, the small physics of power.

This is a deep dive into the fastest 100 in ODI history and the records orbiting it: the sub‑40-ball club, World Cup bullets, by-country sprint kings, and the hidden context that separates a good day from a once-in-a-generation charge. It’s written from a press-box vantage with dressing-room stories and patterns I’ve logged over years on the road. Settle in.

What “fastest century in ODI” measures—and what it doesn’t

- It’s about balls faced to 100, not minutes or overs.

- It makes no distinction between formats of a day game—first innings vs chase both count, World Cup and bilateral ODIs count the same.

- It’s an odd stat in that it’s both indisputable and layered. Two batters can reach 100 off the same number of balls, yet one did it in a handbrake innings where he slowed after a blazing start; the other may have built from 20 off 20 to ludicrous at the death. The record can’t show the shape of the innings, but that shape tells you everything about intent, risk, and control.

The current world record: AB de Villiers’ 31-ball hundred

One innings sits on the mountaintop. AB de Villiers’ 31-ball century against West Indies in Johannesburg is the standard against which every fast ODI hundred is judged. It wasn’t a slog. It was precision. The bat swing was short, the ball selection ruthless, the response to length immediate. He walked in with a platform already built and turned a steep chase for the record into a glide.

Match situation and why it mattered

- South Africa were well set: when you inherit a high-scoring platform with wickets in hand, you can treat every ball like a scoring opportunity and still leave headroom for calculation. De Villiers had that luxury.

- The opposition bowled into his bat arc. Not by design, of course, but the lengths de Villiers adores—hard length and the fraction-full slot—kept recurring. Against a hitter who can open up 360 degrees, even good plans can crack.

- The ground is a factor. Johannesburg’s altitude gives the white Kookaburra that extra carry. Mishits float. Clean hits travel into the crowd like guided projectiles.

How he did it

- Pick-up, not heave. His hands were quiet, shoulders aligned, and the swing plane repeatable. The hard hands he uses in Tests soften in ODIs; he lets the bat work through the ball.

- He moved the field. Those late-cuts and flips over short third drew the fine fielders finer—and then the slog-sweep and the traditional lofted drive exploited the widened outfield.

- He chased the record only when it was safe to. The first part of his assault was clinical. Without telegraphing intent, he allowed the run rate and momentum to bully the opposition before he bullied the record.

Why the venue matters

Johannesburg is a turbo track for power hitters: true bounce, thin air, and boundary dimensions that reward flat trajectories. Add in a fast outfield and a white ball skidding onto the bat, and you have a laboratory for speed.

The sub‑40 club: the rare air of ODI’s quickest

Only a handful of ODI centuries have arrived inside 40 balls. That’s the final frontier of white-ball hitting: where margin for error basically vanishes and a batter lives off every other ball being a boundary.

Sub-40-ball ODI centuries (selected)

- 31 balls — AB de Villiers vs West Indies, Johannesburg — No. 3 — result: win — note: world record

- 36 balls — Corey Anderson vs West Indies, Queenstown — middle-order — result: win — note: broke Afridi’s mark before de Villiers

- 37 balls — Shahid Afridi vs Sri Lanka, Nairobi — No. 3 — result: win — note: record for years; 11 sixes, audacious pinch-hitting masterclass

- 40 balls — Glenn Maxwell vs Netherlands, Delhi — No. 6 — result: win — note: fastest World Cup hundred

Those four bullet points tell a story of eras. Afridi’s innings arrived in the early pinch‑hitting age—rough edges, big swings, and a wild chemistry that made teams rethink the use of No. 3 as a missile. Anderson’s and de Villiers’ came in a refined power era with thicker bats and calmer mechanics. Maxwell’s shows the modern shape of a whirlwind at No. 6: walking into a platform and turning a good day into a once-in-lifetime montage.

Fastest century in Cricket World Cup history

World Cups compress pressure. Tall targets, tight narratives, and opponents who don’t blink. The fastest World Cup century belongs to Glenn Maxwell: 40 balls, a controlled blaze against Netherlands in Delhi that redefined what “on the charge” looks like in tournament cricket.

Why it stands apart

- Tournament context. This wasn’t an end-of-series blowout. Maxwell read the pitch early: skiddy, lowish, and fast enough to trust. He reset lines by shuffling late, forced the quicks to shorten, then picked off spin with quick feet and bottom-hand power.

- The time he chose to go. He waited for a gear shift opportunity: a new bowler, a riskier field, and one loose over to drop the hammer. Batters with fast hundreds all share this timing instinct: the ability to spot when opposition control thins—and to attack that seam relentlessly.

Other lightning World Cup hundreds to know

- Aiden Markram — 49 balls — a crisp, modern powerplay assault that felt like a breathless net session, only with a packed crowd.

- Kevin O’Brien — 50 balls — the blueprint for a chase-shock in the tournament: counterpunching from chaos, picking the straight boundaries, and running like the target belonged to him.

These innings did more than bend a scoreboard. They forced tactical rewrites—how teams handle their fifth bowler, how they pace powerplays, and how long they can afford to hold back a death specialist.

The strategic anatomy of a 30–50 ball hundred

Fast hundreds aren’t random. They’re usually shaped by five parameters:

-

Platform vs rescue

- Platform: Top-order monsters like de Villiers and Maxwell benefitted from starts that lifted pressure. With wickets in hand, risks are easier to price. The innings becomes a game of math—nine overs, sixty balls, eight-to-ten boundaries needed, a handful of doubles—and the batter owns the tempo.

- Rescue: The Kevin O’Brien template is different. That’s crisis batting with controlled aggression: split high‑value zones (straight, midwicket pockets), disrupt the length with late movement, and pick bowlers for targeted damage.

-

Ground geometry and altitude

Johannesburg, Queenstown, Delhi: three very different venues, but all promote speed—high bounce, flat decks, shortish squares or smaller straight boundaries. Big-hitting isn’t only about muscle; it’s about understanding how a 60-meter hit in one venue equals 68 in another.

-

Ball age and type of bowler

New balls travel; old balls grip. Most hyper-fast hundreds lean on making hay before the change-up sticks in the surface. Quick hitters also hunt specific bowler types: back-of-a-length seamers without a disguised slower ball, or spinners without the pace variation to make the batter second-guess.

-

Skill blend: swing speed, leverage, hand speed

The cleanest fast hundreds are about leverage and wrists, not bodyweight. AB de Villiers and Jos Buttler are masters at turning a length ball into a lofted extra-cover stroke without telegraphing intent. Afridi’s violence came with a different truth: a high backlift, a committed downswing, and head stillness that made the ball look bigger.

-

Decision density

You can’t miss many balls if you reach a hundred in 40. Every delivery requires a plan in miniature: where is my single if the boundary isn’t on, what field is being tested, what’s the bowler’s next slower ball? The calm between big shots often defines the ceiling.

Fastest ODI century while chasing: why it’s different

Chasing flips the calculus. Every choice is tethered to the target. The quickest chasing hundreds ask the batter to redraw strike-rate targets over and over without losing the shape of the innings.

Two defining chases:

- Virat Kohli — 52 balls to 100 in a chase against Australia. It was all wrists and angles, the serenity of his best ODI mode. Strike rotation stayed intact even as the boundary count spiked; risk felt rationed rather than improvised.

- Kevin O’Brien — 50 balls to 100 in a World Cup chase that stunned England. The power was honest, the intent obvious, but the genius lay in the overs he chose to cash in: he attacked the fifth bowler, targeted the short side, and left himself a par finish, not a miracle.

These innings underline a principle that coaches repeat privately: smart risk selection under the scoreboard’s shadow is worth more than raw power.

By batting position: where do the fastest 100s come from?

- No. 3 and No. 4: The classical sweet spot. A batter enters early enough to exploit fielding restrictions, late enough to ride a platform. De Villiers at No. 3 is the text‑book: base in, fast hands, all scoring areas open.

- No. 5 and No. 6: The modern engine room. Maxwell’s World Cup thunderclap from No. 6 shows how a late‑innings specialist can now challenge records once thought to belong to top‑order hitters. Shorter time on strike, yes, but a higher “license to fly.”

- Openers: Rarer for a pure sub‑40 since the new ball can bite. When it happens, it’s usually on a true pitch or in a mismatch, with an opener connecting with everything in the V and square.

By opposition: patterns that keep repeating

- West Indies figure in multiple fastest‑hundred scorecards, often because they’ve played on spicy batting decks in high‑scoring series. The flip side: their batters have also produced quick centuries when the pitch is fair.

- Associate teams in World Cups can face a perfect storm: quality hitters in sync, short boundaries, and pressure in fielding execution. Maxwell’s 40-ball World Cup 100 is an example of a heavy favorite maximizing every advantage.

By venue: the stadiums that supercharge speed

- Johannesburg (Wanderers): Friendly bounce, outfield speed, white ball carrying like a drone. It’s an accelerator for batters who hit on the rise.

- Queenstown: Square boundaries that beg for pick‑ups and pulls, and a surface that rewards good hands through the line.

- Delhi: Lower bounce at times but skiddy; when the pitch is fresh and the ball is newer, it can be a runway for players who hit flat.

Top lightning ODI hundreds you need to know

This is a curated list that captures the essence of the record—speed, context, and signature style. It’s not an exhaustive database; it’s the spine of the fastest-century story as it stands.

Selected fastest ODI centuries (ordered by balls to 100)

- 31 balls — AB de Villiers, vs West Indies, Johannesburg — finished 149 — No. 3 — result: win — the gold standard

- 36 balls — Corey Anderson, vs West Indies, Queenstown — finished unbeaten — middle order — result: win — power with a golfer’s swing

- 37 balls — Shahid Afridi, vs Sri Lanka, Nairobi — finished 102 — No. 3 — result: win — pure pinch-hitting chaos, 11 sixes

- 40 balls — Glenn Maxwell, vs Netherlands, Delhi — finished 106 — No. 6 — result: win — fastest World Cup hundred

- 44 balls — Mark Boucher, vs Zimbabwe, Potchefstroom — finished 147* — wicketkeeper’s dream day

- 45 balls — Brian Lara, vs Bangladesh, St George’s — result: win — the silkiest entry on a brutal list

- 45 balls — Shahid Afridi, vs India, Kanpur — result: win — kept launching between cow corner and long-off

- 46 balls — Jesse Ryder, vs West Indies, Queenstown — result: win — clean arc hitting down the ground and through square

- 46 balls — Jos Buttler, vs Pakistan, Dubai — result: win — late movement at the crease and bullet wrists

- 48 balls — Sanath Jayasuriya, vs Pakistan, Singapore — result: win — the original havoc merchant in colored clothing

- 49 balls — Aiden Markram, World Cup match, Delhi — result: win — modern timing clinic

- 50 balls — Kevin O’Brien, World Cup chase, Bangalore — result: win — the defining tournament chase

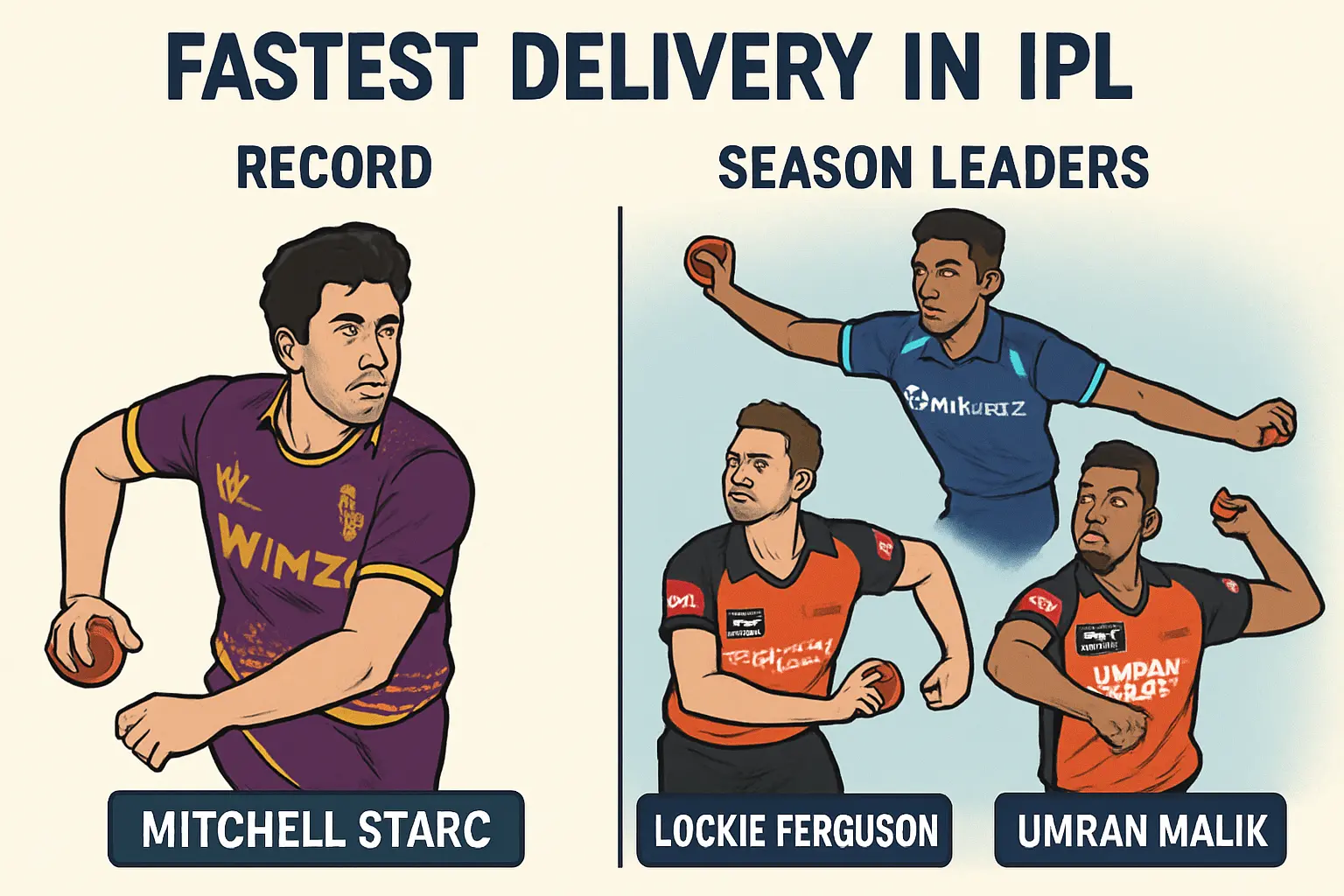

Fastest ODI 100 by country: the current sprint leaders

- South Africa: AB de Villiers — 31 balls. The benchmark at home and worldwide; proof that shape beats swing when it comes to sustained velocity.

- New Zealand: Corey Anderson — 36 balls. Heavy bat speed, low center of gravity, and the confidence to lift on length.

- Pakistan: Shahid Afridi — 37 balls. Unapologetic violence. The innings that turned “pinch-hitter” into an identity rather than a gimmick.

- Australia: Glenn Maxwell — 40 balls (World Cup). Combines bottom-hand force with soft hands to open gaps in front of square.

- England: Jos Buttler — 46 balls. A master of late movement and late hands, and maybe the best at converting a good start into a juggernaut finish.

- Sri Lanka: Sanath Jayasuriya — 48 balls. The original left‑hand disruptor at the top, daring teams to set deep fields in the powerplay.

- India: Virat Kohli — 52 balls (chase). The smoothest of the lot; less about six-count and more about timing the surge exactly when the game asks.

Fastest World Cup hundreds: the elite bracket

In the tournament crucible, speed gets an extra sheen. These are the innings that have shaped how teams script their middle overs and death phases on the biggest stage.

- Glenn Maxwell — 40 balls, Delhi — world record for the tournament; a brutal, logical acceleration that made every ball look slower than it was.

- Aiden Markram — 49 balls, Delhi — an exhibition of early-overs intent meeting strict shot selection.

- Kevin O’Brien — 50 balls, Bangalore — the Chateau Lafite of upset knocks: just the right vintage of audacity and control.

How bat technology and white-ball laws changed the speed ceiling

- Bat profiles. Thicker edges, bigger sweet spots, but crucially, improved pick-up balance. Top players can swing fast without losing shape, which means mis-hits travel, not die.

- Two new balls and field restrictions. With a newer ball at each end for more of the innings, pace on the ball remains available deeper. Reduced sweepers in the ring during specific phases create extra scoring gaps.

- Powerplay literacy. Teams now map out “powerplay ownership” in pre-series planning: who takes the new ball bowlers, who targets which over numbers, and how to transition from 1–10 overs to the later highway without friction.

The risk math behind a 40-ball century

It looks like red mist from afar. From the middle, it’s cold numbers.

- Boundary cadence: to reach 100 in 40 balls, you need roughly 20 scoring shots that go for four or six and a handful of ones and twos. That’s a boundary roughly every other ball, with just enough dots to reset.

- Over targeting: most quick hundreds feature at least two overs worth 20+. The best time to launch is often the first over of a returning pacer or the start of a spinner’s spell before he finds length.

- Variations: batting teams now prep hitter-specific maps—where a batter’s top contact points intersect with a bowler’s slower-ball release. The elite hitters can read seam orientation and release cues, not just length.

Bowling answers: how teams try to defend against a record run

- Wide yorkers with late pace-off: forces an unnatural hitting arc, asks the batter to fetch the ball against the angle, and brings third man and deep point into the game.

- Bouncer and chest-high surprise: used sparingly, then doubled down if the batter’s trigger is reaching across his stumps. The deal-breaker is control; miss short and it becomes a hook-fest.

- Field ploys: bait a hit to the longer boundary with a stacked leg-side outfield, then slide the length to deny elevation. Against 360-degree players, captains now hide their fifth bowler in 1–2 over bursts wrapped by specialists.

Most sixes in an ODI innings—and why it matters here

The fastest 100 in ODI often correlates with a high six count. The ultimate single-innings sixes mark belongs to Eoin Morgan with 17. AB de Villiers has lives near the summit with 16 in his record knock. The note for analysts: a high six-to-four ratio signals bowler mis-lengths and a batter willing to trust elevation on skiddy surfaces.

Related pace records (context you’ll be asked about)

- Fastest fifty in ODI: AB de Villiers — 16 balls. That’s scarcely enough time to memorize bowlers’ lengths, and yet he did. It’s frightening because it obliterates any settling period.

- Fastest 150 in ODI: AB de Villiers — 64 balls. A full-scale demolition that shows the second-stage acceleration is possible without entering slog mode.

- Fastest 200 in ODI: Ishan Kishan — 200 reached in 126 balls. Not a “fast hundred” in the narrow sense, but relevant to the evolution of ODI pace: the modern elite can now stack phases—fast start, mid-overs press, death lift—into double-century arcs.

When “quick” becomes “inevitable”: reading the wrists, not the scoreboard

You can feel a fast hundred coming before the strike-rate tells you. Watch the wrists. Do they close over the ball late, turning a fair length into a screaming square drive? Look at the head position at impact—still and slightly inside the line—and at recovery: the bat return is sharp, not lazy, which means the hitter is set early for the next ball. All of that tells you the bowler has five deliveries to come and the batter feels like he has eight swings left in the over.

Era distribution: pinch-hitters to precision-hitters

- Pinch-hitter origin story: Sanath Jayasuriya and Shahid Afridi created the first template: take the top of an innings and smash a hole in it. Fields weren’t ready; captains hadn’t reimagined their early-over lines.

- The precision wave: AB de Villiers, Jos Buttler, and Glenn Maxwell represent technique-driven speed—late movement at the crease, shorter backlifts, stable bases. They can go just as fast without making the ball feel like a lottery.

- Tournament specialists: Kevin O’Brien and Aiden Markram proved that tournament rhythm can be bent by a single, perfectly timed sprint.

The chase vs set paradox: why speed in the first innings often looks faster

One quiet truth: fastest hundreds skew toward first innings. Here’s why:

- Freedom from scoreboard pressure. Even with a target in mind, the ceiling feels higher when you’re setting: you can aim for 12-an-over without worrying that 14-an-over later will be impossible.

- The “show” effect. Big home crowds, batting paradise decks, and flat Kookaburras in early afternoon—teams often plan to entertain as they accumulate. That entertainment is a byproduct of optimal hitting conditions.

When a record is on: how dressing rooms support liftoff

I’ve sat in rooms where a hitter is on 80 off 30-something and everyone knows. The messages from the balcony are surgical:

- Reminders, not commands: “Stay with your areas,” “He’s gone slower-ball heavy,” “Longer square boundary this end.”

- Hidden logistics: a substitute runs drinks with a freshly scuffed grip or a lighter bat, a throwdown specialist notes the length that’s skidding through. It’s marginal, but it matters.

- In the rooms, no one says it out loud. You don’t jinx a rocket. You just keep the runway clear.

Programmatic angles for data-hungry readers

If you’re building your own tables or filters, these are the fields worth tracking:

- Balls to hundred

- Player

- Runs scored (final)

- Dismissal (or unbeaten)

- Opposition

- Venue

- Batting position

- Match result

- Phase split (balls 1–30 vs 31–60)

- Boundary map (4s/6s)

- Over-by-over pace trend

- Bowling types faced and dismissal risk

A practical, fan-first leaderboard

For quick reference, here’s a compact table with the defining entries for fastest ODI hundreds. It captures the core details; collectors can add their own layers on top.

Fastest ODI centuries (selected, sorted by pace)

| Balls to 100 | Player | Opponent | Venue | Batting position | Final runs | Result | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 | AB de Villiers | West Indies | Johannesburg | 3 | 149 | Win | World record |

| 36 | Corey Anderson | West Indies | Queenstown | 6 | 131* | Win | Record progression |

| 37 | Shahid Afridi | Sri Lanka | Nairobi | 3 | 102 | Win | 11 sixes |

| 40 | Glenn Maxwell | Netherlands | Delhi | 6 | 106 | Win | Fastest World Cup 100 |

| 44 | Mark Boucher | Zimbabwe | Potchefstroom | 5 | 147* | Win | Wicketkeeper blitz |

| 45 | Brian Lara | Bangladesh | St George’s | 3/4 | 117 | Win | Silken power |

| 45 | Shahid Afridi | India | Kanpur | 3 | 102 | Win | Iconic Indo-Pak blast |

| 46 | Jesse Ryder | West Indies | Queenstown | Opener | 104 | Win | Twin thunder show day |

| 46 | Jos Buttler | Pakistan | Dubai | 5 | 116 | Win | Late-crease genius |

| 48 | Sanath Jayasuriya | Pakistan | Singapore | Opener | 134 | Win | Original pinch-hitting template |

| 49 | Aiden Markram | — | Delhi | 4 | 106 | Win | World Cup sub‑50 |

| 50 | Kevin O’Brien | England | Bangalore | Middle order | 113 | Win | Greatest chase-shock |

Note: For comprehensive, filterable datasets (World Cup only, by country, vs team, or by batting position), consult primary match pages and verified records hubs. The numbers above are the widely accepted pace leaders, presented to anchor the story of the record.

What actually improves a batter’s odds of a sprint hundred

- Early contact confidence. Two early boundaries—ideally one on each side of the wicket—turn decision-making from defensive to proactive.

- Reading the seam. White balls that keep a prominent seam after the first few overs help pick slower-ball cues; elite hitters key off seam position to pre-load back-foot or front-foot shapes.

- Non-striker awareness. Great partners feed pace: quick between overs, clear “yours-mine” calls, and the small signals about fielders’ throwing arms that change twos into threes.

Captaincy decisions that either stifle or supercharge the attempt

- Over-resourcing the wrong end. Many captains habitually save their best death bowler for the final overs. Against a red-hot hitter, one well-timed over in the mid-30s can decapitate momentum before it becomes myth.

- Field vanity. Stationing a fielder “to make the batter think” on the rope in a rarely used area is a tax you can’t afford. In these innings, every fielder needs a job that intersects with the hitter’s favorite areas.

- Failure to rotate spin. A spinner who finds his length is gold, but bowling him in one block can be costly. The most effective anti-record tactic is to break rhythm: spin-pace-spin pacing, mixed with unexpected lines.

What the fastest-centuries club tells us about ODI evolution

ODIs are often framed as the patient middle child between Tests and T20Is. The fastest hundred in ODI history rejects that label. It shows an ODI can be as explosive as any format while still rewarding craft. Here’s the truth the record underlines:

- White-ball cricket is converging in the skills it rewards—late hands, power with shape, and decision agility—but ODIs still demand sustaining that skill over 15–25 overs of opportunity, not 6–12. That asks for a deep reservoir of controlled aggression.

- The most modern element of the fastest hundreds? Not the bats. Not the balls. It’s information. Hitting plans are no longer based on “this feels good today.” They are refined, bowler-by-bowler, venue-by-venue, over-by-over. And yet, the essence remains the same: pick length early, swing clean, and trust your eyes.

The FAQs that never go away

Who hit the fastest century in ODI and in how many balls?

AB de Villiers holds the record with a 31-ball hundred against West Indies in Johannesburg. It’s the reference point for every fast ODI 100.

What is the fastest century in Cricket World Cup history?

Glenn Maxwell’s 40-ball hundred against Netherlands in Delhi is the fastest in World Cup history.

Which Indian has the fastest century in ODI?

Virat Kohli owns the fastest ODI hundred by an Indian, reaching three figures in 52 balls during a chase against Australia.

Is AB de Villiers’ record still unbeaten?

Yes. The 31-ball standard stands alone at the top.

Who has the fastest 150 in ODI?

AB de Villiers again, reaching 150 in 64 balls—an innings that maintained shape and clarity even as speed increased.

Tactical notes for coaches, captains, and the next record-breaker

- Build the runway: the majority of sub‑50 hundreds come with a platform. Pick a batting order that gives your best accelerator a high-probability, low-risk entry with at least 20 overs left.

- Map bowlers by phase: some quicks are unhittable with the new ball but predictable second spell. Some spinners are fine in the middle but death liabilities. Launch windows are planned, not stumbled into.

- Train elevation, not just power: on most ODI grounds, flat sixes are the currency of a fast hundred. Practice hitting length over the infield with a repeatable arc that clears the rope by five meters, not fifty centimeters.

- The partner effect: the non-striker who steals singles early keeps the hitter in rhythm. A batter on 60 off 24 who faces three balls in the next three overs can stall. Keep the ball coming back.

A closing note on pace and poetry

The fastest century in ODI history is a number with a heartbeat. It’s a batter telling a story at impossible speed: about range, about courage, about the tiny, private calculations that become public spectacle when bat meets ball just right. AB de Villiers set the mark. Corey Anderson, Shahid Afridi, and Glenn Maxwell stretched it in their own accents. Others will come. They’ll bring bigger bats and richer data and new training lingo to “unlock” speed.

But the thread that connects every lightning ODI hundred runs back to something timeless. See the ball early. Hit it clean. Make the game bend to your will. When that happens, when one player accelerates a day’s cricket so fiercely that everyone else in the ground can only hold on, the fastest century in ODI stops being a record and becomes a feeling you can carry home.

Key takeaways

- AB de Villiers’ 31-ball hundred is the ODI speed crown.

- Glenn Maxwell owns the tournament pinnacle with a 40-ball World Cup century.

- Sub‑40-ball hundreds are rare, shaped by platform, venue, and surgical intent.

- Country leaders: de Villiers (SA), Anderson (NZ), Afridi (PAK), Maxwell (AUS), Buttler (ENG), Jayasuriya (SL), Kohli (IND).

- Related speed marks: AB’s fastest fifty (16 balls) and fastest 150 (64), and Ishan Kishan’s quickest double century progression (200 in 126).

If you care about where cricket is going, not just where it’s been, bookmark these names and numbers. They’re not just records on a page; they’re signposts for the next generation’s imagination.