A double hat-trick in cricket commonly means four wickets in four consecutive deliveries by the same bowler. Only wickets credited to the bowler count; run-outs and similar dismissals do not. Purists sometimes use “double hat-trick” to mean two hat-tricks back-to-back (six in six), but in modern usage across broadcasts, match reports, and dressing rooms, four in four is the standard.

Cricket thrives on nuance, and few topics invite more barstool debate than what exactly constitutes a double hat-trick and which wickets count. This guide cuts through the noise. It is written from the vantage point of someone who has sat in selection meetings arguing over wording in team media notes, scored domestic games where an umpire’s call could make or break a rare sequence, and heard bowlers explain the choreography behind taking four in four. You will find the definitions you need, the edge cases no one else explains, and the context that brings the term to life.

What exactly is a hat-trick and a double hat-trick

The hat-trick is one of the sport’s most cherished milestones: three wickets in three consecutive deliveries by the same bowler. Now translate that to a double hat-trick under modern usage: four wickets in four consecutive deliveries by the same bowler. The operative words are “wickets,” “consecutive,” and “same bowler.” Substitute any of those and the record evaporates.

Some old-school statisticians, leaning on the idea that a “double” should literally be two hat-tricks, use it to describe six wickets in six consecutive deliveries by the same bowler. That view is academically tidy and has admirers, but it is outpaced by contemporary reporting and commentary, where “double hat-trick” practically equals “four in four.” This article treats four in four as the mainstream meaning while describing the six-in-six interpretation wherever relevant.

Which dismissals count toward a hat-trick or double hat-trick

Only dismissals credited to the bowler count. That sounds simple enough until you drill into the dismissal types and the effect of wides, no-balls, and free hits. Here is the clean version scorers and statisticians actually use.

Dismissals that count toward hat-trick and double hat-trick (credited to the bowler)

- Bowled

- Leg before wicket (lbw)

- Caught

- Stumped

- Hit wicket

Dismissals that do not count toward hat-trick or double hat-trick (not credited to the bowler)

- Run-out (including non-striker run-out, colloquially Mankad)

- Obstructing the field

- Retired out

- Timed out

- Handled the ball (now subsumed under obstructing the field by modern Laws)

Wide and no-ball complexities

- Stumped off a wide counts as a wicket for the bowler. It also adds a wide to the bowler’s analysis, yet the wicket stands and can be part of a hat-trick or double hat-trick.

- Hit wicket can occur off a wide or a no-ball. In either case, hit wicket is credited to the bowler and therefore can contribute to a hat-trick or double hat-trick.

- Caught off a no-ball does not count; neither does lbw or bowled. Those are prohibited dismissals off a no-ball for the striker. So a bowler cannot progress a hat-trick on a no-ball unless the batter hits wicket.

If you need a one-glance summary, this is the way scorers teach new colleagues:

| Counts vs Doesn’t Count (for hat-trick and double hat-trick) | |

|---|---|

| Bowled | Counts |

| LBW | Counts |

| Caught | Counts |

| Stumped | Counts (including off a wide) |

| Hit wicket | Counts (even off a wide or no-ball) |

| Run-out | Doesn’t count |

| Timed out | Doesn’t count |

| Obstructing the field | Doesn’t count |

| Retired out | Doesn’t count |

Edge cases explained like you’re in the dressing room

Across overs and across spells

Consecutive deliveries by the same bowler do not need to be in the same over or the same spell. Ending an over with two wickets and starting your next over with two more produces a double hat-trick under the four-in-four definition. The scorebook tracks deliveries bowled by the same bowler; if no other delivery by that bowler without a wicket intervenes, the streak is intact. A fielding side can change ends, change bowlers at the other end, or break for an interval; none of that matters. Only the sequence of balls bowled by the same bowler counts.

Across innings

In multi-innings cricket, a bowler can complete a hat-trick or a double hat-trick across innings of the same match. Taking the last ball wicket of one innings, then taking the first three or three of the next to complete four in four deliveries is valid. Limited-overs cricket uses single-innings formats, so across-innings sequences are not applicable there.

Wides and no-balls: do they break the sequence

Any delivery bowled by the same bowler that does not result in a wicket credited to that bowler breaks the sequence. A wide or a no-ball without a bowler-credited wicket is a delivery in the sequence and ends the streak. This is the part people misunderstand: even though a wide does not count as a legal ball in the over, it is still a delivery. A bowler chasing four in four cannot afford a stray wide between dismissals unless that wide results in a stumping.

Wicket off a wide: stumped and hit wicket

A stumping off a wide or a hit wicket off a wide both count. That means a bowler could, for example, take two wickets, follow with a wide ball that results in a stumping, and then take another wicket next ball to complete a double hat-trick. It happens, rarely, but it counts.

Wicket off a no-ball: the awkward truth

On a no-ball, the striker cannot be out bowled, lbw, or caught. That wipes out the three most common dismissal modes during a hat-trick run. However, the striker can still be out hit wicket off a no-ball. If that happens, the wicket is credited to the bowler and, strangely enough to casual fans, still contributes to a hat-trick or double hat-trick. Also note that a run-out on a no-ball is still a run-out; it does not help the bowler’s sequence.

Free hit

In limited-overs formats, a free hit follows a no-ball. On a free hit, the striker cannot be out by any dismissal that is not allowed off a no-ball. That means no bowled, no lbw, no caught, and no stumped on a free hit. The striker can be out hit wicket on a free hit, as that remains allowed off a no-ball. The striker can also be run-out, but that does not help the bowler. So a hat-trick or double hat-trick is almost always blocked by a free hit unless the batter somehow puts down their own stumps.

Run-out between deliveries

A non-bowler dismissal that happens between deliveries (for example, a timed out, or a batter failing to take the field) does not count for or against the sequence. It neither advances the hat-trick nor breaks it. The next ball the bowler delivers is still the next in that bowler’s sequence.

DRS and overturned decisions

Reviews do not complicate the logic. The outcome that stands at the end of the review is the result of that delivery. If an on-field not out is overturned to out, the wicket counts toward the sequence. If an on-field out is reversed to a no-ball or not out, the sequence is broken accordingly. This matters especially when the third ball of a sequence is tight on height or front foot; bowlers who know they are on two-in-two will often ask the umpire to check the front foot automatically to avoid a nasty post-wicket surprise.

Unusual dismissals

- Non-striker run-out (Mankad): not credited to the bowler, does not count. If it occurs on the relevant delivery, it breaks a hat-trick or double hat-trick attempt.

- Obstructing the field: rare, not credited to the bowler, does not count.

- Timed out: not credited to the bowler, and with no delivery bowled it neither counts nor breaks the sequence.

- Retired out: same as timed out for sequencing purposes.

Double hat-trick vs four-in-four vs six-in-six

Language evolves faster than laws. There is no MCC Law that defines a hat-trick or double hat-trick; these are record-keeping terms. As media grew and compressed descriptions for highlights, “double hat-trick” settled into the meaning that fans recognize instantly: four wickets in four balls by the same bowler. Scorecards use “four in four” or “4 in 4” to avoid ambiguity, and the term has leapt from commentary boxes into playing groups. Players talk about “4 in 4” at training; analysts clip “four-in-four” reels; broadcasters put “Double Hat-Trick” in on-screen graphics.

The purist alternative is internally consistent. A “double” of a thing should be two of the thing. Two hat-tricks back-to-back is six wickets in six balls by the same bowler. This has been used in some quarters and occasionally shows up in historical discussions or pub quizzes. It’s a glorious sequence either way. Just be clear in the conversation you are having: if your audience watches modern cricket, “double hat-trick” maps to four in four. When precision matters, say “four wickets in four balls” or “six in six” and you’ll never be misunderstood.

What wickets constitute a double hat-trick

Think of the double hat-trick as a chain of four consecutive deliveries by the same bowler, each of which must end with a wicket credited to that bowler. That is the entire equation. The four wickets can be any mix of bowled, lbw, caught, stumped, or hit wicket. The four deliveries do not need to be legal balls in over-counting terms, but they must be deliveries, and none of them can be a ball that passes without a bowler-credited wicket. Insert a plain wide, a plain no-ball, or a run-out, and the sequence ends.

A few combinations that explicitly qualify:

- Bowled, lbw, caught in slips, stumped off a wide

- Caught at midwicket, bowled, hit wicket off a no-ball, lbw

- Stumped, caught behind, lbw, hit wicket

- Bowled, bowled, bowled, bowled (dreamland, but occasionally reality)

A few combinations that do not qualify:

- Bowled, lbw, run-out, caught (run-out broke the chain)

- Caught, no-ball (no wicket), lbw, caught (no-ball broke the chain)

- Stumped off a wide, stumped off a no-ball, caught, lbw (stumped off no-ball is not a valid dismissal)

Strategy and psychology: how bowlers actually hunt four in four

Bowlers do not chase statistical ornaments when the game is in the balance. They chase match leverage, and sometimes the path to leverage runs through wicket-taking sequences in clusters. When a bowler is on two-in-two, the fielding side draws a breath; when they are on three-in-three, the stadium thrums. Chasing a double hat-trick is part technical execution, part theatre.

Death-overs blueprints

In T20s and ODIs late in the innings, many four-in-four sequences have started with a yorker that breaches the base of middle stump or a slower ball that tempts a miscue to the deep. At the death, batters premeditate; bowlers exploit that by alternating extremes: a surprise hard length into the hip after a wide-yorker field, a change-up off-cutter after two thunderbolts at the toes. A bowler looking for four in four at the death will usually keep a short midwicket lurking for the miscued slog and retain a slip if they trust the new batter to grope at a fuller line first ball.

Middle-overs mines

In the middle of the innings, captains hunt clusters with leg-spinners and angle bowlers who can turn the game with drift and dip. A leg-spinner setting four in four might use the same seam presentation but alter pace: legbreak, googly, legbreak, topspinner. The finishing delivery is often the simplest: a straighter one aimed at the stumps because fresh batters tend to plant and play around their pads.

Red-ball rhythms

In first-class and Test cricket, four-in-four is rarer but more tactile. Seamers set it up by luring a drive to a packed cordon, then pressing on a good length that sews seam across the top of off stump. The third batter often perishes to the away nip, and the fourth to a fuller one that threatens lbw. Captains who smell four in four will add a short leg or leg gully if the pitch whispers uneven bounce. They also slow the game: time is an ally when nerves are jangling.

The batter’s view

The new batter walking in on a hat-trick ball is a bundle of conflicting advice. “Play late.” “Get forward.” “Expect the yorker.” “Watch for the slower one.” The best counter is a still head and a straight bat. Many double hat-trick fourth wickets happen because the fourth batter assumes the theatre is over. It isn’t. The bowler knows the new batter’s adrenaline is pumping and often goes with the simplest method: stump-to-stump and make them play.

Umpires and reviews

On two in two or three in three, umpires will quietly tighten their routines: a more deliberate look at the front foot, an extra half-tick to judge height for the bouncer. The advice over the radio from the third umpire to check the foot if a wicket falls is routine in professional cricket. That protects the theatre. Nothing kills a double hat-trick faster than a belated no-ball.

Format-specific notes and realities

Double hat-trick in Test cricket

No free hits, longer spells, and spells that cross days create fascinating possibilities. Four in four can cross overs, sessions, and innings. The sequence under pressure is often slip-cordon heavy: two slips, gully, short leg, maybe a leg gully if the ball is biting. Because bowlers can bowl longer, the same bowler can come back with the next new ball and continue a sequence. That is where across-innings double hat-tricks lurk. The flip side is batter resilience; red-ball batters defend better and leave better, making four-in-four monumental.

Double hat-trick in ODIs

Free hits exist, which means a no-ball in the middle of a chase might block a streak unless hit wicket bails the bowler out. The best hunting ground is a collapse beginning at the end of an over: two wickets to finish, two to start the next. Middle-overs leg-spin also plays here; skiddy pace-off can produce a sequence of caught in the ring, lbw on the skidder, and bowled through the gate.

Double hat-trick in T20/T20I

Four in four has a special charged feel in T20 because events are compressed. Sequences often come at the death where hitters swing big and misread changes of pace. Because free hits are common after overstepping, bowlers disciplined at the crease have an advantage. There have been several famous four-in-four bursts in this format; they occupy a special place in T20 lore because they bend win probability in one over.

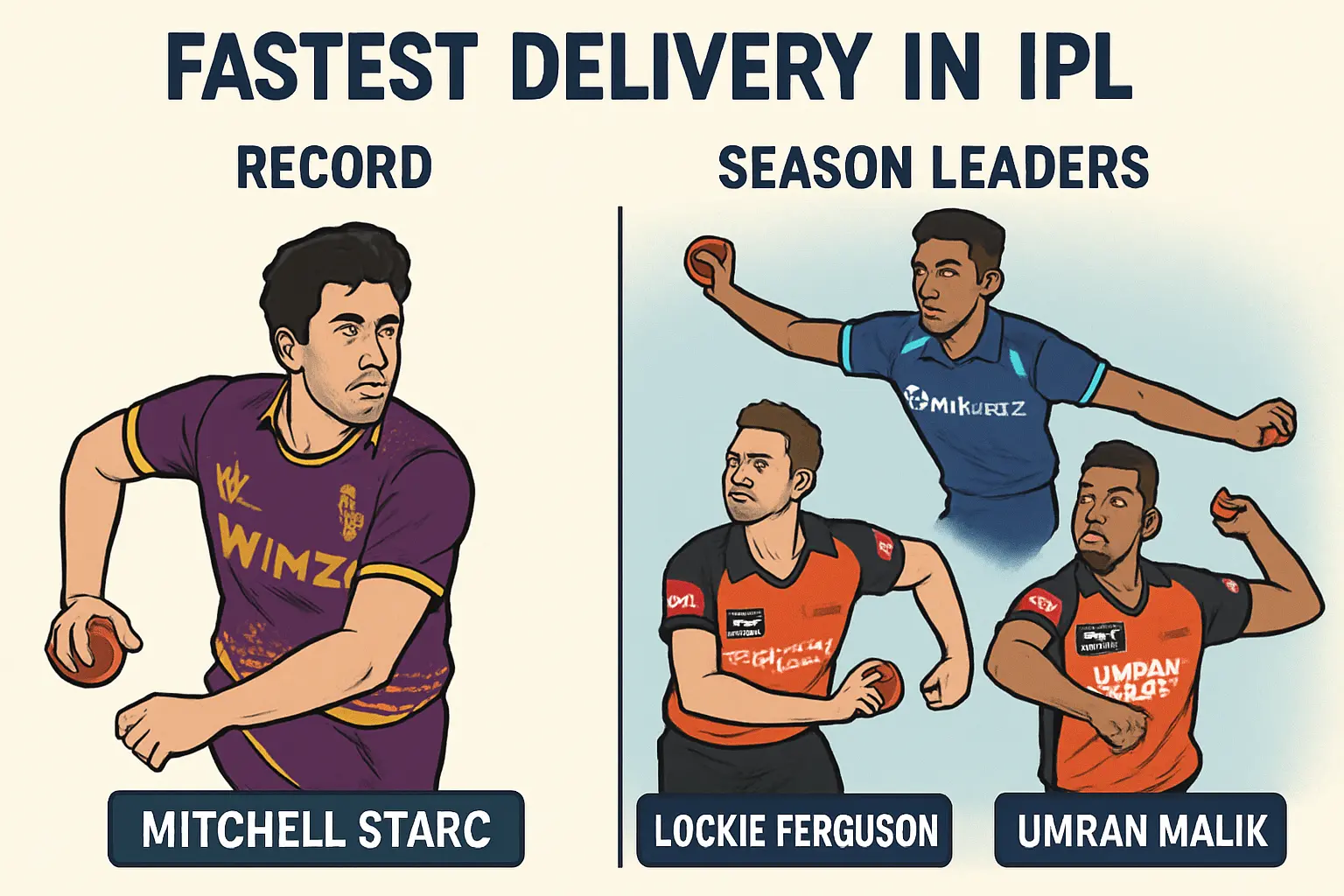

Double hat-trick in IPL/PSL/BBL/CPL/The Hundred

Franchise leagues give bowlers short, clearly defined roles. Captains hold back specialists for specific batters and phases. That can create mini matchups where a bowler faces a string of new batters after a wicket falls. Leg-spinners and slingy yorker specialists have both enjoyed purple patches in these leagues. The tactical environment—overs allocated, fine boundary dimensions, super sub rules in some competitions—can help or hinder sequences. Across these leagues, four-in-four has been rarer than hat-tricks but not unheard of in T20Is played by the same bowlers on the same grounds. In domestic leagues, broadcasters brand four-in-four as a “double hat-trick” without hesitation, and teams lean into the theatre, surrounding the bat on the next ball even in T20.

Double hat-trick in domestic first-class cricket

Longer formats and more overs give rise to spells where a bowler working with a reversing ball or a responsive seam can skittle a tail. Four in four here often includes a mix of caught behinds and lbws as batters of uneven technique face top-end spells. Scorers in domestic games are meticulous about logging across-innings sequences; many of the most artful four-in-four spells have happened quietly on county or state grounds.

Notable four-in-four instances in international cricket

Some moments are etched into highlight reels and coaching clinics alike.

- Lasith Malinga, the master of the toe-crushing yorker, has produced four in four in two international formats. The sling action, the late dip, the cold precision under pressure: it is a blueprint on how to turn a white ball into a scythe. One of those came against a top-tier side in a global tournament; another came in a T20I where he added a five-for to the carnage.

- Rashid Khan unfurled four in four in T20I cricket with the craft of a leg-spinner who reads batters like a book. He set them up with a consistent base speed, then altered the seam tilt to produce a googly that tunneled beneath the bat. That spell is part clinic, part highlight reel.

- Curtis Campher seized the cricketing world’s attention in T20I cricket by harvesting four in four that began with a scramble in the ring and ended with a bewildered middle order. What made it memorable was the audacity to keep targeting the stumps; every ball asked a new, direct question.

- Jason Holder pinned down a double hat-trick in T20I cricket at the death with clever changes of pace and full, straight execution. The way he used his height to get bounce on the hard length ball followed by the fuller killer blow was textbook late-over strategy.

These are the emblematic examples. Four-in-four has also popped up in women’s internationals and in domestic competitions on every continent. Each instance underscores a common theme: patience for the setup, nerve for the finish.

Team hat-trick vs bowler hat-trick

A team hat-trick is three wickets in three balls for the fielding side, irrespective of who delivers them. It could be bowler A taking a wicket, followed by a run-out off the next ball, and then bowler B starting the next over with another wicket. That is a team hat-trick, not a bowler hat-trick. Likewise, a “team double hat-trick” could be four wickets in four balls shared across bowlers and dismissals, including run-outs. Broadcasters sometimes mention the team sequence to celebrate the collapse; statisticians keep the bowler sequence distinct because that is the rarer, personal milestone.

Bowler hat-trick and double hat-trick demand that each wicket arises from the same bowler’s delivery and is credited to that bowler. If a run-out sits in the chain, the chain breaks for bowler accounting even if the team goes on a wicket spree.

Records and near-mythic sequences

Four in four is already uncommon. Five in five and six in six are bordering on myth. Yet the sport has a remarkable way of writing new parables.

- Five wickets in an over is possible. It usually requires a combination of wickets and a wide or no-ball that adds an extra ball or two to the over, because a standard over has only six legal deliveries. Where it has happened, it invariably involves tailenders, hurry, and panic.

- Six wickets in six deliveries by the same bowler is the purist’s “true double” hat-trick. Consider the ingredients: no wides or no-balls without bowler-credited wickets, six batters in a row succumbing to bowler-credited dismissals, and a captain brave enough to attack for every ball. The images you conjure—packed slips, helmeted ring fielders, a bowler sprinting back to mark—are cricket’s addictive drama.

- Consecutive wickets record talk can include variants like “seven wickets in ten balls” or similar clusters that stretch the imagination. Those celebrate collapses more than pure consecutive-delivery art, but they live in the same aura.

Rare cricket dismissals and hat-trick eligibility

Part of the confusion stems from scorebook minutiae. A few oddities to keep straight:

- Stumped off a wide is a wicket for the bowler and counts.

- Stumped off a no-ball is not a thing; stumped cannot occur off a no-ball.

- Hit wicket can occur off anything legal enough to put the ball in play, including wides and no-balls; it counts and is credited to the bowler.

- Handled the ball became subsumed into obstructing the field; neither count to the bowler.

- Non-striker run-out, even when executed by the bowler, remains a run-out in accounting terms and does not count to the bowler’s hat-trick.

Scoring and notation: how the book records a double hat-trick

When scorers record a four-in-four, they track the sequence by the bowler’s deliveries, not by over balls alone. The notation might show:

- Ball by Bowler X: W (lbw)- Next ball by Bowler X: W (caught)- Next ball by Bowler X: Wd+W (stumped off wide)- Next ball by Bowler X: W (bowled)

Even though the wide does not count as one of the six legal balls in the over, it is still a delivery, and the wicket is tallied for the bowler. If a no-ball precedes a hit wicket, the scorer will mark NB + W (hit wicket). Over-by-over summaries might show an over lengthened by an extra ball or two; what matters for the sequence is the unbroken chain of bowler-credited wickets across deliveries by that bowler.

Umpires signal stumped even on a wide and confer with the scorers to ensure both the wide and the wicket are logged for the same ball. Good scorers will also annotate the double hat-trick in the margins with a small star or capital note because history deserves ceremony.

Free hits complicate the chase aesthetically

When a team bowls a no-ball and offers a free hit, a bowler on a hat-trick or double hat-trick rarely gets a chance to finish the run because the striker cannot be dismissed bowled, lbw, caught, or stumped on that free-hit delivery. That said, a batter can still be out hit wicket. There have been heart-in-mouth moments where a batter loses balance or treads on the stumps trying to manufacture room. It is the only realistic path through a free hit for the bowler’s sequence.

Hat-trick vs double hat-trick: the difference in language and feel

- Hat-trick

- three wickets in three consecutive deliveries by the same bowler. It is both a milestone and a momentum swing. The ball goes from a spotlight to a talisman.

- Double hat-trick (modern)

- four wickets in four consecutive deliveries by the same bowler. It turns a match, steals breath, and etches a name in commentary folklore. The fourth ball brings a pressure only the player in that moment understands.

- Double hat-trick (purist)

- six wickets in six consecutive deliveries by the same bowler. Think of it as two hat-tricks with no air in between. Few players will ever even stand on the edge of this cliff.

How many wickets is a double hat-trick

Under the dominant modern usage, a double hat-trick equals four wickets in four consecutive deliveries by the same bowler. Under the stricter “two hat-tricks in succession” view held by some, a double hat-trick equals six wickets in six consecutive deliveries by the same bowler. Match reports, highlight packages, and broadcasters overwhelmingly use the four-in-four meaning today. When clarity matters, say “four wickets in four balls” or “six wickets in six balls.”

Which wickets count for a hat-trick and a double hat-trick

This is the central confusion point for many fans. Bowler-credited dismissals: bowled, lbw, caught, stumped, hit wicket. Wides and no-balls do not cancel those dismissals if the Law allows the dismissal on that delivery type. That gives us the two surprising inclusions:

- Stumped off a wide counts toward a hat-trick or double hat-trick.

- Hit wicket off a wide or off a no-ball counts toward a hat-trick or double hat-trick.

Everything else—run-out, obstructing the field, timed out, retired out—does not.

Four in four in the wild: the shapes these spells take

Late-over meltdown

The classic T20 shape: tailenders and lower-middle order trying to turn twos into sixes. Ball one is a yorker smashing the base. Ball two is a slower ball into the pitch, miscued to long-on. Ball three is the batter’s first look; the bowler goes fuller and straighter, lbw. Ball four is panic; hit wicket as the batter backs away too far or an inside edge cannoning into the leg stump.

Middle-overs squeeze

Spin in the ring. Ball one: a legbreak drawing the big sweep, top edge to deep square. Ball two: a googly for the new batter, pad before bat. Ball three: same seam, quicker, caught at slip off the face. Ball four: topspinner skidding on, defended onto the stumps as hit wicket. Every piece of that chain is within a leg-spinner’s normal plan; it is the execution under pressure that knits it into a double hat-trick.

New ball storm

Seam upright, slip cordon hungry. Ball one: away nibble, caught at second slip. Ball two: fuller and straighter, lbw to the inward shape. Ball three: back of a length and across, nicked. Ball four: wobble seam on a good length, inside edge onto pad then onto leg stump. Sometimes the fourth is the easiest because the batter expects the grand deception when the bowler simply does the basics better than anyone else in the ground.

Regional meaning and quick translations

In South Asian conversation, the phrase “double hat-trick” is commonly used to mean four in four. Everyday renderings:

- Hindi: Double hat-trick ka arth aam taur par chaar gendon par chaar wickets hota hai.

- Urdu: Double hat-trick se murad aam tor par char gend par char wickets hoti hain.

- Tamil: Double hat-trick enbathu pothuvaga naangu ball-il naangu wicket-ugal.

- Telugu: Double hat-trick ante sadharananga nalugu ball-lalo nalugu wickets.

- Bengali: Double hat-trick mane sadharonoto charte ball-e charte wicket.

These phrases mirror how TV anchors and radio commentators explain the term on broadcast. In print and on team sheets, you will still see “four wickets in four balls” used for absolute clarity.

Practical double hat-trick rules compiled

- Consecutive deliveries by the same bowler are the only clock that matters. Over breaks, innings breaks, and field changes do not interrupt that clock.

- Any delivery by the same bowler without a bowler-credited wicket breaks the sequence. That includes a plain wide or no-ball.

- Stumped off a wide counts; hit wicket off a wide or no-ball counts.

- Caught, lbw, or bowled cannot occur off a no-ball to the striker. Those are not available routes during a no-ball or free hit; a bowler cannot complete a double hat-trick via those on such deliveries.

- Run-outs never count to the bowler. Even a non-striker run-out effected by the bowler does not contribute to the sequence and, if it happens on the delivery, breaks it.

- Timed out and retired out do not count and do not break the sequence because no ball was delivered.

- Reviews adjust the outcome of the delivery. Whatever the final decision is after DRS or third-umpire checks is what the record books keep.

Bowling figures and legacy

A bowler who completes a double hat-trick enters a rarefied club. The figures also acquire a special texture in post-match analysis because four wickets in four balls often come with a small economy footprint for the passage. That means the spell has leverage: not only were wickets clumped, runs were throttled. Analysts look at the “impact over” by plotting expected runs vs actual; a four-in-four shift typically yanks win probability by double digits. In the dressing room, those overs are replayed in little circles for months.

How captains and fielders support the attempt

Captains go bold. They add catchers, even in white-ball formats where a misfield can turn the momentum back. The best captains balance the pull of the theater with the needs of the game: it is one thing to push up a second slip on a hat-trick ball in the powerplay, quite another to give away the single that allows a set batter to keep strike at the death. You will see a mid-off come up, a leg slip appear, and a short midwicket sharpen, because single-denial and mistake-forcing are how the fourth wicket materializes.

Fielders, in particular wicketkeepers, become the bowler’s shadow. On a hat-trick or double hat-trick ball, keepers read the bowler’s plan and adjust leg-side takes for slower-ball lines or widen their stance for the potential wide that invites a stumping. Slip fielders quietly close the angle by a step or two. Fine margins become the difference between folklore and a near-miss.

Umpiring pragmatics and etiquette

At professional level, umpires will slow the tempo slightly when a bowler is on three in three. They will ensure both batters are ready, the field is counted, and the front foot is watched by the book. Fielding captains sometimes ask for the front-foot check after a wicket; many modern officials will do it automatically on such pressure balls. At community level, scorers and umpires often take pride in getting the details pristine: few moments in grassroots cricket bring more shared joy than logging a double hat-trick correctly.

Why definitions matter for records, broadcasts, and memory

Words in cricket accumulate meaning by use. When broadcasters say “double hat-trick,” they align public memory in a particular direction. When statisticians publish records, they freeze the definition. Fans deserve clarity. Four in four is the mainstream definition now; six in six is a beautiful, stricter usage that will always have a following. Keeping both in mind enriches the conversation rather than narrowing it.

Declarative answers to the most argued scenarios

- Run-outs do not count in a hat-trick

- A run-out is not credited to the bowler. If a run-out occurs on the delivery that would otherwise be part of the sequence, the chain breaks for the bowler’s hat-trick or double hat-trick.

- A wide without a wicket breaks the sequence

- A wide is still a delivery. If no bowler-credited dismissal occurs on it, the sequence ends. The over receives an extra ball, but the streak does not survive the wide.

- A wicket off a wide can count

- If the batter is stumped off a wide, or hits wicket while the delivery is called wide, the dismissal is credited to the bowler; it counts toward the sequence.

- No-ball dismissals almost never help; hit wicket is the exception

- On a no-ball, the striker cannot be out bowled, lbw, or caught. The only route to a bowler-credited wicket aside from an extremely unusual obstruction scenario is hit wicket. If the striker dislodges the stumps, the bowler gets the wicket, and it contributes to the sequence.

- A hat-trick and a double hat-trick can span overs and even innings

- As long as the deliveries are consecutive deliveries bowled by the same bowler, spanning overs is fine. In multi-innings matches, ending one innings with a wicket and starting the next with more is eligible.

- A free hit almost always stops a hat-trick attempt

- Because the striker cannot be out bowled, lbw, caught, or stumped on a free hit, the usual dismissal methods are off the table. Hit wicket remains possible and is the only realistic route on a free hit.

- Stumped off a wide counts; stumped off a no-ball does not

- A stumping off a wide is valid and credited to the bowler. A stumping off a no-ball cannot occur.

- Timed out never counts and does not break the sequence

- Timed out does not arise from a delivery and is not credited to the bowler. The next ball bowled by the same bowler remains the next in the sequence.

- Non-striker run-out (Mankad) does not count

- Even though the bowler can effect the dismissal, it is recorded as a run-out. It does not add to the sequence and breaks it if it occurs on the relevant delivery.

- Retired hurt or retired out does not affect the chain of deliveries

- Because no ball is bowled, the sequence neither advances nor breaks. The next delivery by the same bowler is still the next in the sequence.

- Team hat-trick is not the same as a bowler hat-trick

- Team sequences can include run-outs and different bowlers. Bowler sequences must be bowler-credited wickets on deliveries by the same bowler.

- DRS decisions fix the delivery outcome for the record

- Whatever the final decision after review becomes the official result of that delivery and is used in hat-trick and double hat-trick accounting.

The cultural weight of four in four

Cricket is storytelling stitched over statistics. A double hat-trick gives you both: a stat that survives across eras and a story that becomes a campfire anecdote. It’s the spell colleagues mention when contract renewals come up. It’s the passage coaches clip and play for academy bowlers learning how to build pressure and humility at the same time. Fielders remember where they were standing. Keepers remember the noise of the edge. Captains remember the hush before the fourth ball. And the bowler, if you sit them down months later, will tell you about a heartbeat that slowed rather than quickened on that last run-up.

Concise takeaways for fans, scorers, and players

- Double hat-trick in cricket most commonly means four wickets in four consecutive deliveries by the same bowler.

- Only dismissals credited to the bowler count: bowled, lbw, caught, stumped, hit wicket.

- Stumped off a wide and hit wicket off a wide or no-ball do count; caught, lbw, or bowled off a no-ball do not.

- Wides and no-balls without a bowler-credited wicket break the sequence.

- Free hits block most dismissal modes; hit wicket remains the lone exception.

- Sequences can span overs and, in multi-innings formats, cross innings in the same match.

- Team hat-tricks are different from bowler hat-tricks; run-outs help the team but not the bowler’s sequence.

- Modern media and most players use double hat-trick to mean four in four; six in six remains a purist alternate definition.

Conclusion

The romance of cricket lies in the small print as much as in the spectacle. “Wickets constitute a double hat-trick” may sound like lawyer language, but inside it is the heartbeat of the game: craft, nerve, and clarity. Count only what the bowler earns. Respect the chain of consecutive deliveries. Embrace the clean surprises—stumped off a wide counts, hit wicket off a no-ball counts—and know what breaks the spell. Four in four is the modern game’s double hat-trick; six in six is its austere cousin. Both are raptures worth chasing, and both are understood best when the definitions are clear and the stories are told with care.